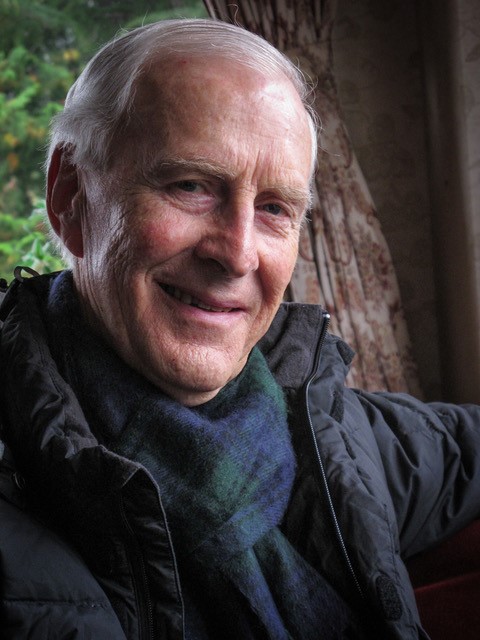

How did you get into Geophysics?

I began my BSc in Canada studying physics, but quickly realised that while the subject sounded impressive, few people were actually hiring physicists. The idea of spending four years at university only to end up working in a bike shop didn’t seem like the best return on investment! Early on, I discovered geophysics—essentially physics applied to the Earth—and it immediately resonated with me. After all, many industries need to “see” into the ground, from oil and gas to archaeology and construction.

Most geophysicists gravitate towards the oil and gas sector because of its size and generous salaries, but I’ve always taken the road less travelled. I focused my studies on near-surface imaging—looking for shallow minerals, buried structures, and underground utilities. By my second year, I’d become fascinated by a relatively new technology called Ground Penetrating Radar. I could see its potential across a wide range of industries. With some financial help from my mother (which I still haven’t repaid!), I bought my first GPR unit and started a company that’s still operating today. Thus far I’ve personally worked in 108 countries on six continents (but still haven’t gotten to Antarctica).

Can you give us insight into what this technology does and why it is so crucial?

I’ve spent most of the past 35 years working with GPR on some very unusual projects—ranging from mapping nickel deposits deep in the jungles of Madagascar, to hunting for buried treasure in Indonesia, to detecting clandestine tunnels under contested borders. Radar is an incredibly versatile tool. It’s used in mineral exploration, utility mapping, archaeology, precision agriculture, forensic investigation, and even in biomedical imaging. One of the most exciting recent applications is mapping soil moisture in 3D to optimise crop yields. The same underlying technology that can help detect tumours can also measure the thickness of Greenland ice sheets to depths of more than 3 km. The potential is virtually limitless.

You've been involved in projects from the moon’s surface to treasure hunting to the Pyramids of Giza. What have been your favourite projects to date?

Nothing quite compares to working at the Giza Pyramids. These monuments represent one of humanity’s most extraordinary achievements, and yet we still don’t fully understand how they were built—or more intriguingly, what lies inside. These types of projects require highly customised radar systems, often designed to fit through incredibly tight spaces. Everything from the mechanical structure to the data processing algorithms takes months to prepare. When we finally get a system inside one of these ancient structures, we just hope all the modelling and engineering pays off. Sometimes it does… sometimes it doesn’t!

In recent years, you've appeared on TV series like Lost Gold of the Aztecs, The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch, The Curse of Oak Island, and Arabian Adventures: The Secrets of the Nabateans. What has that experience been like?

Several years ago, I received a call from a television production team asking if I could bring a custom-built GPR system to the southwestern United States to help locate a specific target. I agreed, and it turns out I actually love being on camera—and seem to be reasonably good at explaining complex science to a general audience. That first appearance led to more opportunities, and it’s grown from there. These projects are genuinely fun and allow us to experiment with ideas that would be far too ambitious (or eccentric) for commercial projects.

What brought you to UC and New Zealand to study your Master of Science?

For me, UC was the product of a perfect storm. In the late 1990s, I was trialling the use of GPR to explore nickel laterite deposits, a particular type of ore found in tropical regions. I wanted to pursue a Master’s degree to validate the concept, but I also needed access to real exploration data. I managed to secure sponsorship from two Canadian mining companies with projects in New Caledonia—so being based in the Oceania region made sense.

Back in the pre-Internet days, finding a university with GPR expertise wasn’t straightforward. But in 1994, at a conference in Los Angeles, I met a Canadian professor who had just taken up a role at the University of Canterbury and was actively working with radar systems. That encounter made the decision easy. I’d already fallen in love with the South Island from travels with my family in the 80s, and studying in such a beautiful, welcoming place felt like a natural fit. I’ve never regretted it.

If you could offer one piece of advice to a new graduate, what would it be?

In this new world shaped by AI, I’m more convinced than ever that success comes from developing deep, specialised expertise. It’s far better to take some calculated risks and become highly skilled in one niche area than to follow the crowd. Sooner or later, someone will need exactly what you’ve mastered—and when they do, they’ll come looking for you.

Do you have any final thoughts or reflections?

My time at UC was absolutely formative. The South Island is a stunning place to study, and the Kiwi mindset—resourceful, innovative, and a bit humble—has left a lasting impression on me. New Zealanders have always had to punch above their weight to compete on the world stage, and that determination has led to extraordinary contributions in science, sport, and beyond. If I had the chance to do it all over again, I’d head straight back to Christchurch.

Hear from Dr Jan Francke on The Freeman Files Podcast here.

More alumni stories

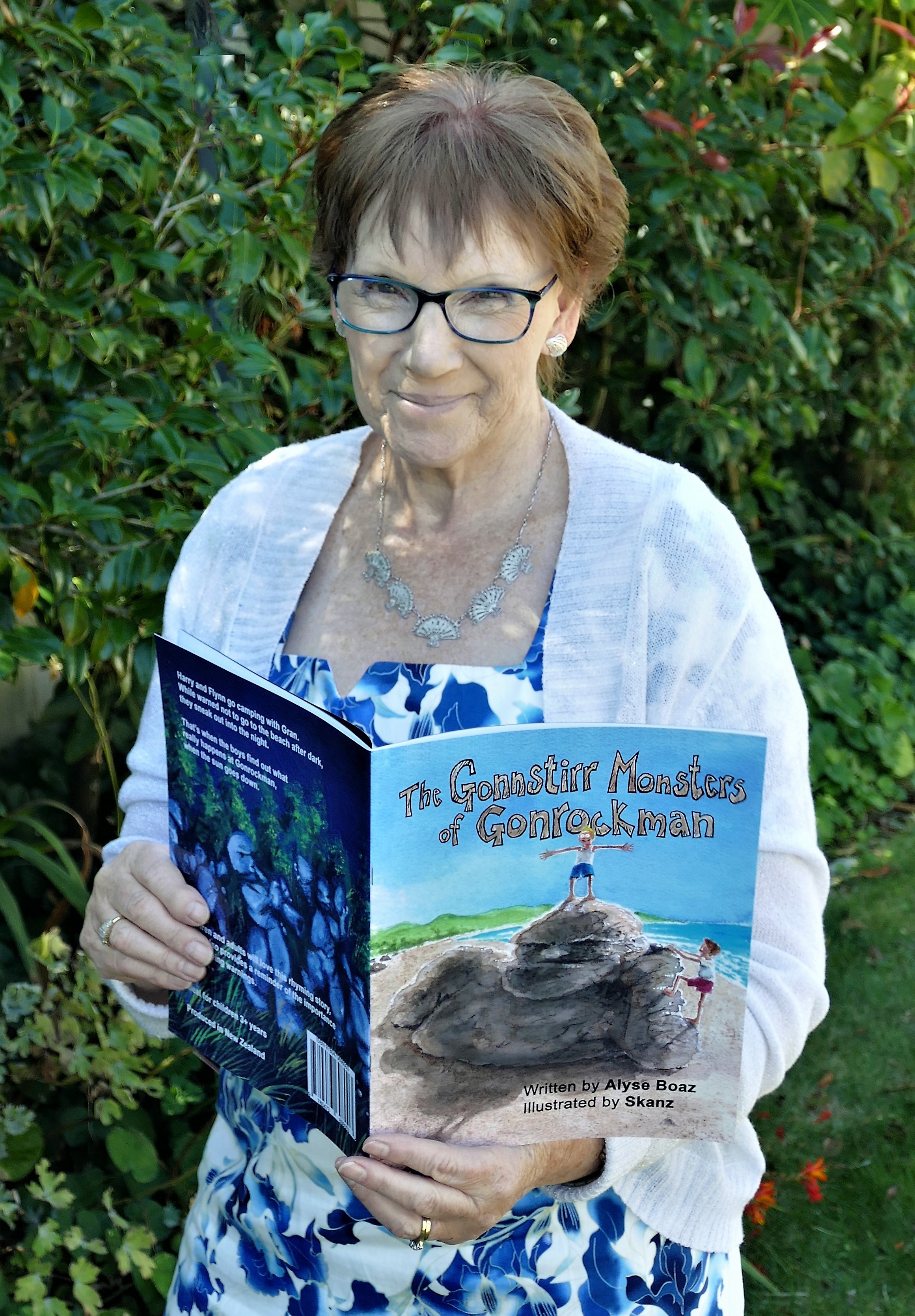

David Garrett

07 November 2025

BSc Chemistry 2007, BSc(Hons) Chemistry 2007, PhD Chemistry 2011

CEO and Co-Founder, The Carbon Cybernetics Group

Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering, RMIT University