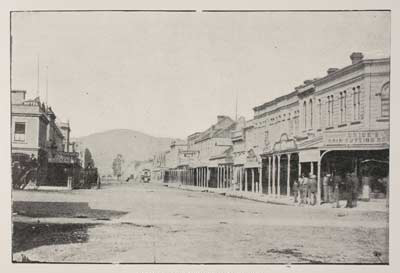

Early Christchurch was essentially a village of wooden cottages and shops, which would have seemed desolate to newly arrived colonists. According to one settler it was “an odd, straggling place. Small wooden buildings dotted about with little pretension to regularity, rough wooden palings for enclosures..."

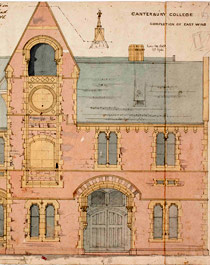

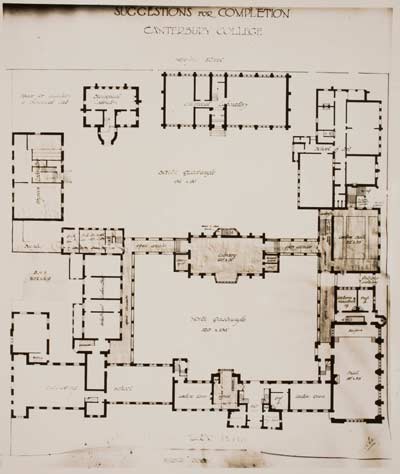

With the appearance of grander stone buildings from the 1860s onwards, locals could begin to feel reassured and proud that their city would indeed become a small slice of ‘home’. By 1886 buildings like those of the Cathedral, the Museum, and the College enabled the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia to claim “Two features at once arrest the attention of the travelled visitor. The first is the thoroughly English look of the place… Nothing is here to suggest pronounced colonial peculiarities.”