From the early writings of Swedenborg, Spiritualism developed into a popular ‘alternative’ spirituality in Britain and America during the nineteenth century, combining the mysterious and the theatrical. It fed from a number of contemporary cultural trends and factors: from frequent liberal perceptions that traditional religion had been discredited by modern science, that science itself was soulless and ill-equipped to offer spiritual satisfaction, as well as a desire to create a form of religion firmly yoked to science, one which would not only stand up to sustained investigation, but ally itself to the optimism characteristic of the era. From a series of paranormal occurrences in the United States, Spiritualism devoured the yearnings of its age, claiming to be the spiritual fulfilment of modernity. Some moderns would be impressed, others distinctly less enthusiastic.

History of Spiritualism

The rappings of the Fox Sisters in upstate New York during 1848 began a craze for séances in nineteenth century America, where a system of patterns ‘raps’, or disembodied taps on wood, allowed the spirits of the deceased to send messages to the world from their astral afterlife. The Fox sisters were exposed when the ‘spirits’ turned out to be their nimble feet, which were revealed on close inspection. The sisters died in poverty, but set up an accepted pattern for subsequent mediums. The distinctiveness of American Spiritualism can be assessed by its debut in the eclectic mixture of American religious life, as well as its egalitarianism. However, the movement quickly came to an end in the United States amidst the chaos of the Civil War in the 1860s, and subsequent debunkings by detractors. From there, however, it spread to Britain, where it was firmly established in the second half of the nineteenth century.

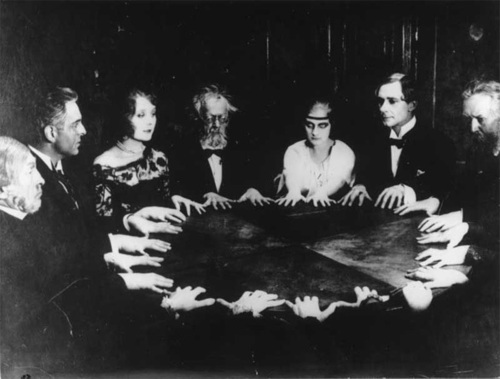

A Still from Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, Fritz Lang's 1922 film which treated occult themes. Spiritualism was reaching its zenith by the interwar period.

A number of distinctive factors can be associated with the appeal of Spiritualism. Perhaps most alluring was its apparent proof for the immortality of the soul, a deeply rooted belief called into question by contemporary philosophical trends, now demonstrated empirically before an audience. On a more earthy level, it was also popular due to the prominence given to women, whose wild on-stage performances formed a sharp contrast with the virginal restrictions on middle-class female behaviour characteristic of Britain and America in the 1800s. Rappings, loud cries of messages from the other world, and the dramatic stage persona of the medium allowed women to be uninhibited in public whilst retaining respectability. The ever-present difficulty, of course, was for the medium to continue ‘performing’ under the increasingly strict test conditions needed to prove their truth. Florence Cook, one of the celebrated mediums of the 1870s, saw her initially strong apparitions become increasingly feeble as the pressure mounted, despite her protests that overt test-conditions frightened spirits away. Many mediums had their reputations broken and died in poverty; those found to have faked apparitions by foot-tapping or forged ectoplasm were usually exonerated by their followers, who claimed that the later forgeries only occurred due to intrusive conditions. In addition to test conditions, this also meant the theatrical side of affairs, namely the need to contend with an abusive audience. After the medium Annie Fairlamb resigned from her society, she blamed frequently hostile audiences (‘the alcoholic element’) who taunted her when materialisations were not forthcoming. The result was that, although initially liberating for many women, fashionable spiritualism could leave them trapped in dubious surroundings.

The world of spiritualism, both a quest for scientific rigour and spiritual meaning, was effectively the child of increasing secularisation, and the Victorian quest for novelty amidst conventional society. For some, it was a liberation from the stultifying formality of bourgeois mores, for others a sign of absurd credulity. When G.K. Chesterton complained that when men do not believe in God, they believe in everything, joined the exasperations both of clergymen and academics at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Bret E. Carroll, Spiritualism in Antebellum America (Bloomingdon and Indianapolis, University of Indiana Press, 1997), 21, 38 , 121

Alex Owen, The Darkened Room: Women, Power and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England (Philadelphia, University of Pensylvania Press, 1990)