The Bible was the first text to be produced using a system known as 'printing with moveable type'. Canterbury possesses a facsimile of this work, known today as the Gutenberg Bible.

The Gutenberg Bible was produced in the German city of Mainz in the early 1450s. Containing a version of Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, there is little that is novel about the text itself. Yet the Gutenberg Bible represents a technological leap forward comparable to the development of the World Wide Web.

Johann Gutenberg's key innovation was the process of printing with moveable type. By 1450, printing was a centuries old technology in Asia, and European presses had been publishing images, and sometimes text, for over half a century. Prior to Gutenberg, however, an entirely new woodcut or engraving was required to print each individual page. The distinctiveness of Gutenberg’s system lay in the creation of a frame and individual letters which could be re-arranged in it. This technique made printing large quantities of text economical as it allowed one set of letters to be used to print multiple pages.

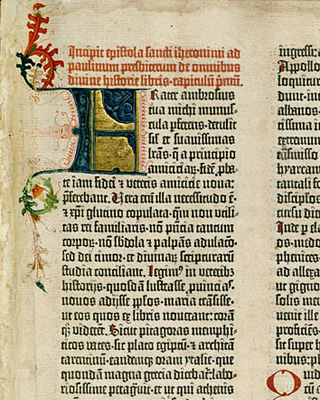

Each copy of Gutenberg’s Bible, in common with many early printed books, was laboriously finished by hand. The tendency to embellish the two columns of printed text reflects the fact that printing by no means brought an instant end to the work of illuminators. Nevertheless, moveable type enabled the learning of the Renaissance to be disseminated in ways that were previously unimaginable.

Amidst new scientific knowledge and texts not seen since the fall of Rome, European scholars found tools that enabled them to reconsider the Bible itself. In the first half of the 16th century, reformers such as Martin Luther built on this. They used Gutenberg’s technology to popularise not only new ideas but new versions of the Bible.