At the time of James I's succession to the English throne in 1603 England was a powder keg of political and religious tensions. These strains were encapsulated in the varied English Bibles available. The same word might, for example, be translated ‘Church’ or ‘congregation’. The latter was a choice welcomed by reformers but anathema to traditionalists who much preferred the former. More disturbingly, from the perspective of James’s government, readers might encounter a preference for describing rulers as ‘tyrants’ in works such as the Geneva Bible.

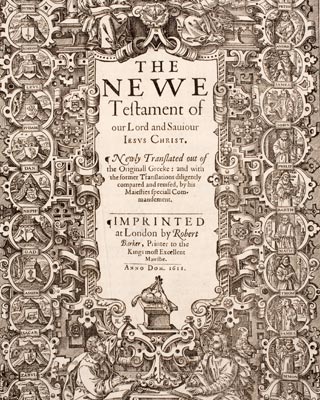

James called the various factions together in 1604. One of the key outcomes of this Hampton Court Conference was the decision to produce a new translation of the Bible, one that would, it was hoped, be acceptable to all sides. In 1611 the project culminated in the KJB.

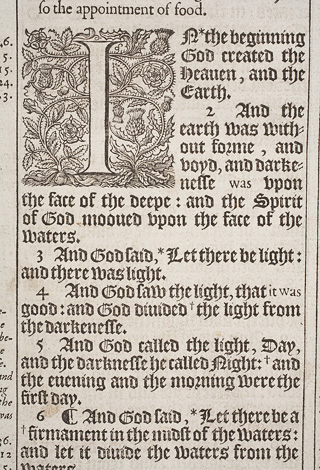

The KJB is distinctive for a number of reasons. It excludes, for example, the detailed – and controversial – explanatory notes that opposing sides incorporated into most translations. First and foremost, however, it is one of few success stories that can be ascribed to a committee. No lead translator was appointed. Instead, the work was apportioned to six ‘companies’ based at Oxford, Cambridge and Westminster. Rather than starting entirely from scratch, their approach was to draw on the existing translations, both Catholic and Protestant, in combination with the latest scholarship.

The translators ranged from the flamboyant Oxford scholar Sir Henry Savile, to the ill-fated John Overall, Dean of St Paul’s cathedral. Sir Henry’s other activities included international travel, translating the Roman historian Tacitus and lecturing on astronomy; John Overall’s disastrous marriage to a much younger woman, ‘bosom’d like a swan’, was the source of much public amusement during the project.

Boris Johnson, the Mayor of London, reads Isaiah 11:1-9 from the KJB: