The striking Red Mountain in Fiordland National Park, West Coast, owes it’s distinctive red colour to oxidisation of heavy metals within the dunite and peridotite rocks, representing ancient deep oceanic crust. The rocks are so high in heavy metals, plants struggle to grow, and those that do are unique to these soils! Our plate boundary and the Alpine Fault along the Southern Alps has shifted these rocks a vast distance apart, with more dunite to be found in Dun Mountain (the rock’s namesake!) and the Maungakura Red Hill in the Tasman region.

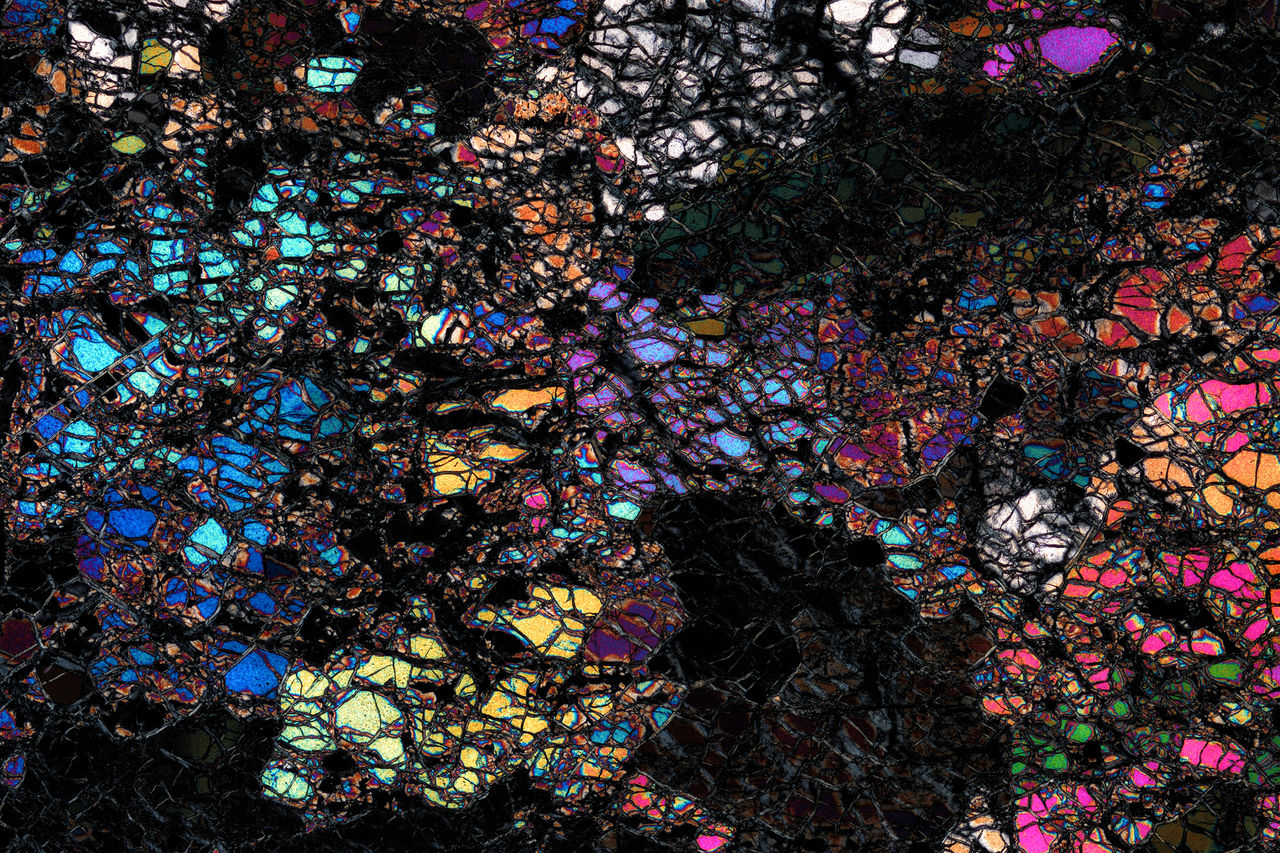

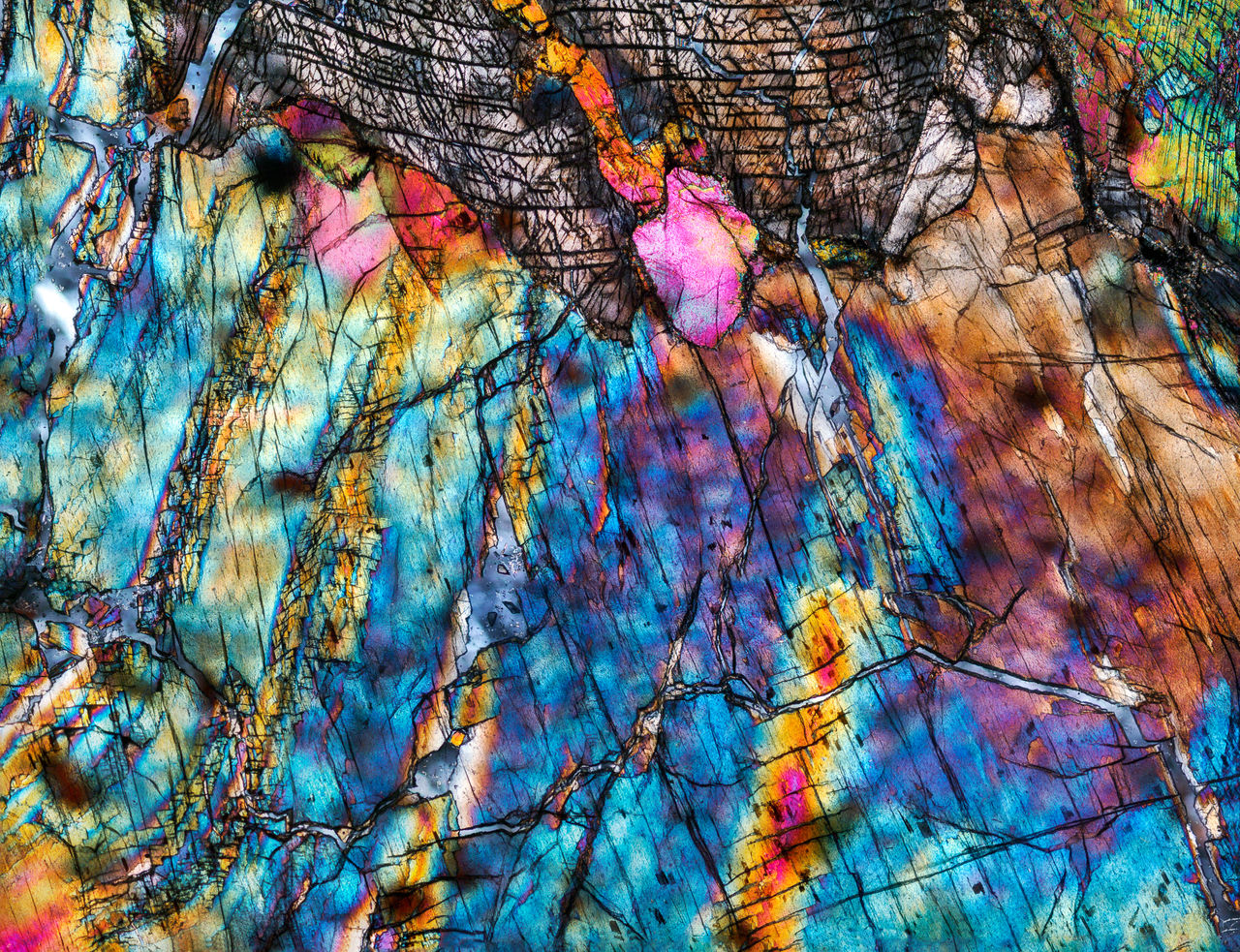

When not oxidised, dunite is a green coloured rock, made up of the mineral olivine. It is a plutonic igneous rock. The rocks in this garden have also been partially serpentinised, which means they have been subjected to fluids and are starting to change under metamorphism. Dunite has this unique ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it, making it a climate change fighting rock! It is currently the focus of significant research into it's many uses.

Ultimately with more time, pressure and fluids, these rocks become fully changed under metamorphism to the taonga that we know of as pounamu or New Zealand greenstone, a collection of nephrite and serpentinite rocks, each one with unique geochemistry, like fingerprints, tracing exactly where each has come from in the landscape.

Kāi Tāhu are the kaitiaki or guardians of pounamu, and each one’s unique mineral signature allows manawhenua and science to work together to protect this precious taonga (treasure).

Kāi Tāhu have a very well-known pūrākau (legend) about the pounamu guardian taniwha Poutini, of which the West Coast region is named for, often in battle with the guardian of sandstone, Whatipū, one of the key rock types traditionally used to grind and shape the much softer pounamu. As Te Reo is an oral language, pūrākau are useful ways to retain knowledge and pass it down through the generations, in an easy to remember format. Many pūrākau record significant geological events and observations of the accompanying geological processes, particularly with respect to volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and floods. From a geological perspective, there are a few key points to this particular pūrākau that address not only the mineral properties of pounamu and sandstone, but also the origins of pounamu, linking it with metamorphism and derivation from the Earth’s mantle (effectively the “blood” of the planet), and provide the first geological map of New Zealand, communicating the locations of the important resource stones used and traded by Māori.