“We set it aside because we really didn’t know what had happened. But then some undergraduate project students tested it for the self-cleaning performance, and it was so photocatalytically active without any UV radiation that we knew we had discovered something new.”

TiO2 is used in sunscreens because it has the ability to absorb radiation. This action creates energy, which is expressed as oxygen ions and oxygen ions are deadly to bacteria. TiO2 is therefore ideal for use on surfaces such as door handles in environments where sterility is a priority, such as hospitals.

Professor Krumdieck pioneered the innovative coating technology during her PhD at the University of Colorado in Boulder, United States, and continued her research in New Zealand at UC, winning a Marsden Fund grant to explore pulsed-pressure vacuum processing, which had not been used before in research or in industry. This was followed by a competitive funding grant with colleague Professor Mark Jermy to collaborate with a top university in Taiwan.

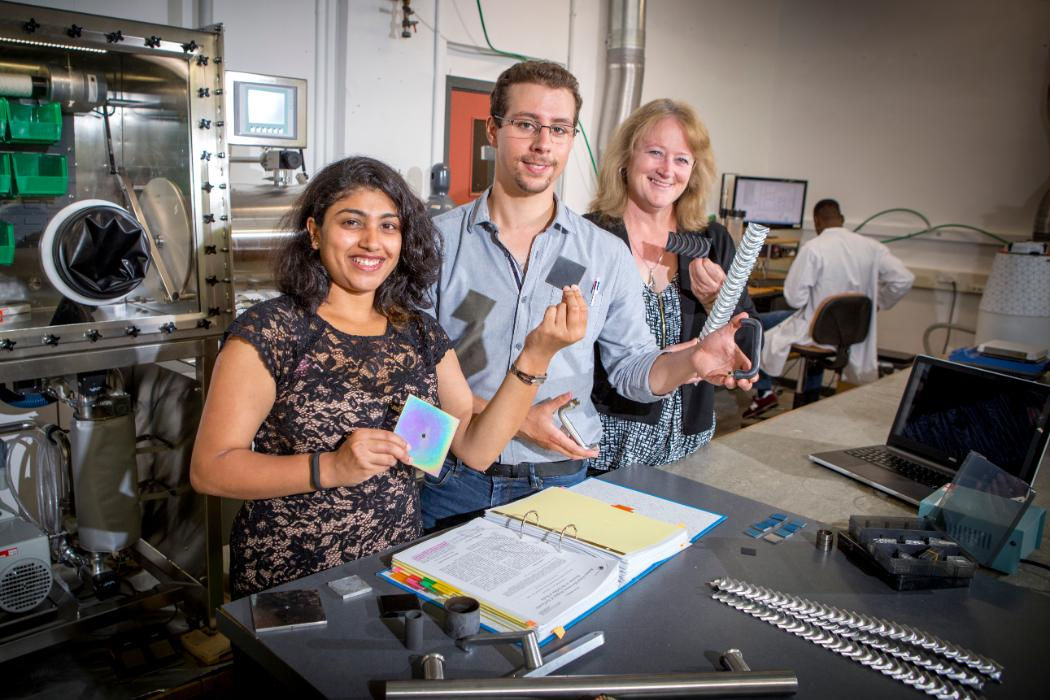

However, Professor Krumdieck and her team of 14 interdisciplinary UC researchers still had two challenges to overcome – how to fix a TiO2 coating onto something like a door handle, and how to activate it without UV radiation. The new black TiO2 held the key to both.

Research collaborator Tim Kimmett at Callaghan Innovation helped to solve the puzzle.

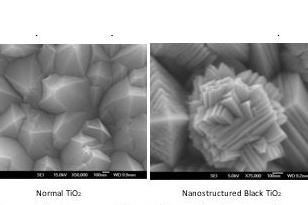

“We spent a fun science day playing with the Scanning Electron Microscope and X-ray diffractometer and really marvelling at how different this material was. We knew had had a new material due to the strange nanostructures we were seeing, and of course the striking black colour,” Professor Krumdieck says.

A few months later Professor Krumdieck was awarded a visiting researcher fellowship at Université Grenoble Alpes in France and took a few of the black coating samples with her. Researchers at the SiMAP Institute were intrigued that the material could be the same as white TiO2 according to analysis, but instead of the typical smooth pyramid crystals of TiO2, the French team, led by Professor Raphaël Boichot, found that the crystals were nanostructured in ways previously only possible by hydrothermal growth of individual nanoparticles.

“Professor Boichot suggested that the material could have visible light antimicrobial activity. When I got back to UC, I was lucky to run into Professor Jack Heinemann who is an expert in microbiology, and he worked with his students to set up a testing system,” Professor says.

“Sure enough, the bacteria did not stand a chance – even after a short time in visible light.”

With no need for radiation to energise the new form of TiO2 and an altered nanostructure that enables the compound to be fixed in coatings, the conditions are right for the multi-disciplinary team to move ahead to developing commercial applications.

The UC researchers have successfully deposited the black coating onto a door handle, and are now working with several companies to complete the engineering development science needed for designing and upscaling for advanced manufacture. Interested international companies are watching progress and hoping the black TiO2 will soon be warding off germs on hospital bed rails and door handles around the world.

The research has been published in Nature magazine: Scientific Reports, vol. 9, Article: 1883 (2019), titled: Nanostructured TiO2 anatase-rutile-carbon solid coating with visible light antimicrobial activity, by Susan P. Krumdieck, Raphaël Boichot, Rukmini Gorthy, Johann G. Land, Sabine Lay, Aleksandra J. Gardecka, Matthew I. J. Polson, Alibe Wasa, Jack E. Aitken, Jack A. Heinemann, Gilles Renou, Grégory Berthomé, Frédéric Charlot, Thierry Encinas, Muriel Braccini & Catherine M. Bishop.

The UC research team includes:

- Matt Watson, Chemical and Process Engineering

- Vladimir Golovko, Chemistry

- Darryl Lee, Mechanical Engineering

- Sam Davies, Engineering Management

- Johann Land, CVD Process Engineering

- Matthew Polson, Chemical Characterization

- Alibe Wasa, Microbiology

- Ethan Yuang, Numerical Modelling

- Susan Krumdieck, Mechanical and Materials Engineering

- Aleksandra Gardecka, Photochemistry

- Catherine Bishop, Materials Science

- Rukmini Gorthy, Materials Characterization

- Sarah Masters, Chemistry

- Jack Heinemann, Biology

-43%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)